|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

He felt that the successful delineation of an object’s form must come before any attempt to reveal its spirit (Binyon, 1911). He encouraged sketching from nature to help the artist capture important details of external form. Ōkyo attracted many followers, including Goshun Matsumura who started his career as a Nanga-style artist. Goshun added the self-expression of Nanga to Ōkyo’s realism to create a style called Shijō. The word Shijō refers to Fourth Avenue (i.e., Shijō-dōri 四条通) in the city of Kyōto where Goshun and his followers had their workshops. Because the Shijō style is so similar to that of Ōkyo Maruyama the term Maruyama-Shijō is used to refer to their combined styles. Neither Ōkyo nor Goshun published any woodblock-printed pictures of flowers and birds. They were strictly painters. However, in the nineteenth century a number of their followers published woodblock-printed, art instruction books that included flower-bird pictures. Some of these artists also illustrated poetry. Each of these two uses for Maruyama-Shijō- style flower-bird pictures is described in more detail below.

Woodblock-printed art instruction books were published to provide aspiring artists and others with examples of the Maruyama-Shijō style. Books with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.10. About half of these books featured copies of paintings by famous Maruyama-Shijō artists, including Ōkyo Maruyama and Goshun Matsumura. The other half included original pictures by a single artist who was usually one of the Shijō branch of Maruyama-Shijō artists.

Table 3.10. Publication date and author of art instruction books with flower-bird pictures drawn in the Maruyama-Shijō style. Pictures were either drawn by a single artist (blank) or by more than one artist (*). Book titles are included in Chapter 4 under the authors’ names.

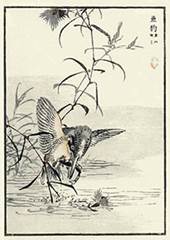

Two pictures from each of these two types of art instruction books are included in Figure 3.20 to illustrate the Maruyama-Shijō style. Shapes of flowers and birds were drawn using a combination of lines and areas of pigment. In some cases a black line was used to outline partially the shape (Figure 3.20d). In other cases no black outline was used (Figure 3.20a,b,c). Shapes of objects drawn by Maruyama-style artists were very accurate (Figure 3.20a) while those drawn by Shijō-style artists were less accurate (Figure 3.20b,c,d). The use of color by artists of both the Maruyama and Shijō branches was similar. Colors were typically accurate, muted and graded. Accuracy was achieved through the use of a wide range of colors which matched those seen in nature. Color was applied as a wash which caused it to be muted rather than bright. Bright color was reserved for highlights such as the yellow beak of the bird in Figure 3.20d. Color was applied unevenly, ranging from dark to light, to simulate shading. This gave objects a three-dimensional look. To help reveal the spirit of flower and bird subjects, they were often arranged diagonally (Figure 3.20c,d).

Figure 3.20. Four flower-bird pictures drawn in the Maruyama-Shijō style. The first two are woodblock-printed copies of paintings by famous artists and the last two are woodblock-printed originals by other artists

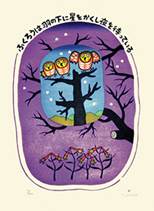

Published poems were sometimes accompanied by pictures drawn by Maruyama-Shijō artists to enhance the mood or theme of the poetry. These poem-pictures were published either as a group in a book or individually as a surimono print. The poetry was mostly kyōka in books and haikai on surimono. For an explanation of surimono, kyōka and haikai see section 3.5.4 Poetry Illustration under the Ukiyo-e School above. Two examples of poem-pictures which featured flowers and birds are given in Figure 3.21. The first example is a surimono print and the second example is taken from a book. Pictures on surimono were usually relegated to the side or corner of the print because they accompanied a large amount of poetry. In books, poems were printed one per page which allowed the accompanying picture to occupy a larger portion of the page. Stylistic features of both surimono and book poem-pictures were comparable to those appearing in the art instruction books described above.

Figure 3.21. Two examples of flower-bird pictures drawn by Maruyama-Shijō artists to illustrate poetry.

A new style of Japanese art called Maruyama-Shijō first appeared in the late eighteenth century. The word Maruyama is the surname of one of the school’s co-founders, Ōkyo Maruyama. The word Shijō refers to Fourth Avenue in the city of Kyōto where the school’s other co-founder, Goshun Matsumura, practiced his art. Ōkyo was the first Japanese artist to adopt realistic features of European-style art that appeared in natural science books imported by Dutch visitors to the port city of Nagasaki. Goshun tempered Ōkyo’s realism with the self-expression and creativity that he had used earlier as a practitioner of the Nanga style, which originated in China. Thus, the Maruyama-Shijō style was a mixture of European realism and Chinese expressionism. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Maruyama-Shijō (MS) style is its use of muted and graded color. Color was applied as a wash which muted otherwise bright colors. Color was applied unevenly in a gradient from dark to light , giving objects a three-dimensional look by simulating shading, The resulting color scheme was much more accurate than that of Nanga-style (N) pictures (i.e., color accurate for 65% MS versus 12% N of pictures included in this analysis). While muted, unevenly-applied color also characterized Nanga-style pictures, color was blotchy rather than graded which reduced its accuracy. Nanga-style pictures also included fewer colors than Maruyama-Shijō-style pictures, making it more difficult to reproduce the color scheme of flowers and birds as seen in nature. The shapes of flowers and birds were more accurate in Maruyama-Shijō-style (MS) pictures than in Nanga-style (N) pictures (i.e., shape accurate for 57% MS versus 31% N of pictures included in this analysis). The fact that only 57% of Maruyama-Shijō-style pictures had accurate flower-bird shapes may be surprising considering that Ōkyo Maruyama embraced European realism. Shijō artists took a less realistic approach to create the shapes of objects, reflecting the Nanga preference for creativity and self-expression. As a result, only slightly more than half of Maruyama-style and Shijō-style pictures, when combined, had accurate flower-bird shapes. To help reveal the spirits of their flower-bird subjects both Maruyama-Shijō (MS) and Nanga (N) artists typically placed flowers and birds on a diagonal (i.e., 72% MS and 77% N of pictures included in this analysis). However, other features such as showing birds in an active position or with rough body-edges were less evident in Maruyama-Shijō-style pictures than in Nanga-style pictures (i.e., birds in an active position for 54% MS versus 71% N of pictures and rough bird body-edges on 16% MS versus 55% N of pictures). This difference reflects the less expressive attitude of the European-influenced Maruyama branch of the Maruyama-Shijō School for whom the revelation of spirit was secondary in importance to the realistic depiction of external form. Most flower-bird pictures drawn in the Maruyama-Shijō style were published in art instruction books in the nineteenth century. A few others were published in poetry books or individually as surimono. Maruyama-Shijō surimono were both larger in size and contained a larger amount of poetry than their Ukiyo-e-style counterparts.

3.10 Style 7 - Nihonga School 日本画派 In the 1850s the Tokugawa government relaxed its policy of restricting Dutch traders to the port city of Nagasaki by opening more of its ports to the Dutch and to other Europeans plus Americans. It was forced to do so because two hundred years of relative isolation had left Japan far behind western nations in military technology. To avoid being invaded and colonized the Japanese government accepted terms of trading agreements that greatly favored their new western trading partners. Government leaders also began a program of military, economic, social and political reform to narrow the gap between Japan and more powerful, industrialized western countries. The objective of this modernization program was to make Japan the equal of western countries in terms of world power and influence. To achieve this objective government leaders championed all things western, including art. Schools were set up to provide training in applied art and fine art as it was practiced in the west. Later, training in traditional Japanese-style art was added to the curriculum. From this training program emerged a new style of art that combined stylistic features of the traditional Maruyama-Shijō, Nanga and Ukiyo-e Schools with a large dose of western realism. This new style was called Nihonga (日本画) which means Japanese (Nihon) Painting (ga). The word Nihon was chosen to distinguish it from Yōga (洋画) which was the name coined for western (yō) oil-painting. Nihonga-style art was admired not only by the Japanese but also by westerners. This was especially true for woodblock prints which found their way to Europe and America in two ways (Brown, 2006). First, they were one of the products featured in the Japanese government’s pavilion at World Fairs held throughout Europe and America between 1873 and 1910. Second, they were imported by art dealers and sold in retail shops to satisfy the demand for Japanese decorative objects created by their earlier appearance at World Fairs. The term Shin Hanga (新版画), meaning new (shin) woodblock print (hanga), was applied to Nihonga-style woodblock prints to help separate them from the Ukiyo-e-style woodblock prints produced earlier. Flower-bird prints were popular with westerner viewers likely because it took little understanding of Japanese culture to appreciate their beauty (Brown, 2005). Woodblock prints featuring flowers and birds were used in three ways; namely, wall decoration, art instruction, and nature appreciation. Each of these three uses is described in more detail below.

Nihonga-style flower-bird pictures were sold individually for wall decoration in both Japan and the west. Three examples are shown in Figure 3.22 to illustrate elements of the Nihonga style. Artists adopted the western practice of accurately depicting the external form of their subjects. The color scheme was typically true to life as well. Accuracy is a notable feature of the Nihonga style. Most artists followed the Maruyama-Shijō practice of using short lines to outline only partly the shape of an object and applying color unevenly in a graded fashion to simulate shading (Figure 3.22a). Some other artists followed the Ukiyo-e practice of outlining an object completely and filling the outline with color applied evenly (Figure 3.22b). Only a few followed the Nanga practice of eliminating the outline for an object and applying color unevenly in a blotchy manner (Figure 3.22c). This preference of Nihonga artists for the Maruyama-Shijō style reflects its more western leanings. To help reveal the inner spirit of flower-bird subjects Nihonga artists used the same devices as artists of other Japanese schools. Birds and flowers were often arranged diagonally (Figure 3.22a,c). Some birds were given rough body-edges (Figure 3.22a) or shown in an active position (none in Figure 3.22). Nihonga artists chose a much wider range of flower and bird species for their subjects than did their predecessors from other schools. Species included exotics from America (e.g., Figure 3.22b) in addition to the European and Asian exotics chosen previously (e.g., bird in Figure 3.22a). Species with symbolic association were chosen (e.g., flowers in Figure 3.22a,c) but so were many more species without any symbolic association (e.g., birds in Figure 3.22a,b,c). The inclusion of more species without a symbolic association may reflect the fact that the target audience for these prints was no longer exclusively Japanese and many of the new western audience members would not be aware of such symbolism.

Figure 3.22. Three examples of Nihonga-style flower-bird pictures used for wall decoration.

Nihonga artists who drew decorative flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.11. Most were active during the first half of the twentieth century when western demand for Japanese flower-bird prints was strong (Newland, Perrée and Schaap, 2001). Koson Ohara was the most notable flower-bird print artist from this period. He and Rakusan Tsuchiya each produced more than one hundred different flower-bird designs. Well known contributors from other periods are Kiyochika Kobayashi (1850-99), Tōshi Yoshida (1950-present) and the father-son duo Shōkō and Atsushi Uemura (1950-present).

Nihonga artists published three different types of art instruction books; namely, copy books for students, books of models for craftsmen, and books to provide examples of their work for those interested in the Nihonga style. Each of these three types of books is described below. Copy books for students taking art classes were published in large numbers between the 1880s and early 1900s. Authors of books with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.12. Some of these artists were influential painters of the time (i.e., those asterisked in Table 3.12).

Table 3.12. Publication date and author of copy books with flower-bird pictures drawn by influential Nihonga painters (*) and other artists (blank). Book titles are given in Chapter 4 under the authors’ names.

Pictures in these books were intended to be traced or copied by students to help them develop basic drawing skills. Consequently, many of the pictures were relatively simple. Two examples are given in Figure 3.23. The shapes of flowers and birds were drawn accurately using either a partial or complete outline. Most pictures were multicolored and color was typically graded (Figure 3.23a) rather than uniform (Figure 3.23b).

Figure 3.23. Two examples of flower-bird pictures from copy books published by Nihonga artists.

Books of models for craftsmen were also published in large numbers between the 1880s and early 1900s. Each book included drawings of both living and non-living subjects to provide craftsmen with a wide range of ideas for decorating consumer goods. Authors of books with flower-bird models are listed in Table 3.13. Of these authors, Ginkō Adachi was the most prolific contributor to this type of art instruction book. Each model was relatively small in size which allowed more than one to be placed on a single page. Two book pages are shown in Figure 3.24 as examples. The small size of models made it difficult to show the shape of all objects accurately. Flowers and birds were usually less accurately drawn than those in the copy books described above. In addition, the color scheme was typically inaccurate because too few colors were used. The fact that these pictures were only intended to be models for other products may explain why accuracy was sacrificed.

Figure 3.24. Two examples of book pages of flower-bird pictures from books of models for craftsmen published by Nihonga artists.

During the 1890s and early 1900s books were published to provide examples of the emerging Nihonga style. These books included works either by a single artist or by a group of artists. Authors of books with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.14. Gessai Fukui edited a number of the books published in the 1890s.

Not surprisingly, the pictures in these books had the same stylistic features as Nihonga pictures sold individually for wall decoration. Three examples from the twenty-five volume set of books edited by Seitei Watanabe (1892) are shown in Figure 3.25. Flowers and birds were depicted accurately and in full color. Color was either graded (Figure 3.25a), blotchy (Figure 3.25b) or applied evenly (Figure 3.25.c). Graded color was the norm as was the use of a partial outline (Figure 3.25a,b) instead of a complete outline (Figure 3.25c) for the shape of flowers and birds.

Figure 3.25. Three flower-bird pictures drawn in the Nihonga style from a set of books edited by Seitei Watanabe (1892).

Flowers and birds were the exclusive subject of books published for people with a keen interest in nature. This audience included westerners as well as Japanese. Nihonga artists who authored these flower-bird books are listed in Table 3.15. Bairei Kōno is the most notable of these artists. He published both the first and the most (i.e., six) flower-bird books. His style is also evident in books published by seven of the other artists listed in Table 3.15. Of the remaining artists, Keinen Imao is best known. His four-volume flower-bird book was one of the objects sold by the Japanese government at international World’s Fairs (Maeda, 1999).

Table 3.15. Publication date and author of Nihonga-style flower-bird books. Authors whose books were similar in style to those of Bairei Kōno are asterisked. Book titles are given in Chapter 4 under the authors’ names.

Three pictures from these flower-bird books are given in Figure 3.26 to illustrate their stylistic features. The shapes of both flowers and birds were typically drawn very accurately using a partial outline (Figure 3.26a,b,c). In contrast, the color scheme was not typically accurate. Only about 30% of pictures had color that was true to life and graded to simulate shading (Figure 3.26a). Color was less accurate and blotchy on another 10% of pictures (Figure 3.26b) and even less accurate on the remaining 60% of pictures because too few colors were used (Figure 3.26c). The limited use of color in pictures intended for an audience with a keen interest in flowers and birds is both surprising and puzzling. Color is not only important for species identification but it is also why many people enjoy looking at flowers and birds. Perhaps the higher cost of multicolor printing combined with the fact that flower-bird books would not appeal to everyone made it too expensive for the majority of flower-bird books to be printed with full color. To help reveal the spirit of their flower-bird subjects, artists often showed birds in an active position (Figure 3.26a,c) or arranged diagonally with flowers (Figure 3.26a,b). Birds were sometimes also shown with rough body-edges (Figure 3.26c).

Figure 3.26. Three examples of pictures from flower-bird books authored by Nihonga artists.

In the 1860s the Japanese government began a program of modernization by adopting the policies and practices of American and European countries. This program fostered the development of a new style of art that combined western realism with stylistic elements of the Maruyama-Shijō, Ukiyo-e and Nanga Schools. This new style was called Japanese Painting (Nihonga) to separate it from the totally western-style of painting done in oil (Yōga). Artists trained in the Nihonga style made a large number of woodblock prints featuring flowers and birds. These prints were published either in book form for art instruction and nature appreciation or sold individually for wall decoration. The latter were called New Woodblock Prints (Shin Hanga) to distinguish them from Ukiyo-e-style prints made earlier for the same purpose. The western realism component of Nihonga was most apparent in the shape of objects. Nihonga artists drew flowers and birds more accurately than their predecessors from other schools. Of the pictures examined for this analysis, 82% had accurately drawn flowers and birds compared with only 30-57% of pictures drawn by artists of other schools. Stylistic elements of the Maruyama-Shijō, Ukiyo-e and Nanga Schools borrowed by Nihonga artists include their use of color, the devices used to reveal the inner spirit of flowers and birds and their choice of flower-bird subjects. Nihonga artists only partly colored flower-bird pictures drawn as models for craftsmen, similar to Ukiyo-e artists. Full color was used on pictures drawn for wall decoration. Of the pictures included in this analysis, color was applied unevenly in a graded fashion on 84%, unevenly and blotchy on 5% and evenly on 11%. The use of graded versus blotchy versus even color followed the practice of Maruyama-Shijō versus Nanga versus Ukiyo-e artists, respectively. Pictures in flower-bird books were either partly colored (55%) or fully colored (45%). The choice of partial color was unexpected because full color was used for flower-bird books published earlier by Ukiyo-e artists. The use of partial color meant that not all Nihonga-style flower-bird pictures had an accurate color scheme. To reveal the inner spirit of their flower-bird subjects Nihonga artists used the same stylistic devices as other schools. Birds were shown in an active position on 50% of the pictures included in this analysis, with rough body-edges on 31% of pictures and arranged diagonally with flowers on 60% of pictures. These percentages are consistently lower than those for Nanga and Ukiyo-e pictures and more similar to those of Maruyama-Shijō pictures (see Figure 3.3 for the actual percentages). It appears that western-influenced Nihonga and Maruyama-Shijō artists were less concerned about revealing inner spirit than Chinese-influenced Nanga and Ukiyo-e artists. The species of flowers and birds chosen as subjects by Maruyama-Shijō, Ukiyo-e and Nanga artists were often symbolically associated with human emotion or with a season of the year. Nihonga artists continued this practice. Of the pictures examined for this analysis, 89% included at least one species with a symbolic association, compared to 93-96% of pictures for the other three schools. However, Nihonga artists also incorporated many other species (i.e., 71 flowers and 62 birds) not chosen by artists of other schools and none of which had a symbolic association. There was less incentive for Nihonga artists to restrict themselves to species with cultural relevance because their audience included westerners who were unlikely to understand fully any symbolic association.

3.11 Style 8 - Sōsaku Hanga School 創作版画派 In the 1860s the Japanese government adopted the western ideal of a society composed of individuals rather than social classes (i.e., Confucian four-class system) as part of its program of modernization. Western individualism was fully embraced by some artists because it championed self-expression and creativity. These artists practiced either western oil-painting (Yōga) or, starting in the early 1900s, a new style of wooodblock print making called Sōsaku Hanga (創作 版画). The term Sōsaku Hanga means creative (sōsaku) woodblock print (hanga). To maximize the opportunity for creativity and self-expression artists took control of the design, woodblock cutting and printing steps in the print making process. Previously, an artist had submitted his design to other craftsmen who cut the woodblocks and then printed the design. This practice meant that the artist’s initial design could be modified, either intentionally or unintentionally, by the block cutter or printer. By controlling all aspects of the print making process the artist guaranteed that the print fully expressed his intent. The initial audience for Sōsaku Hanga was exclusively Japanese but after World War II the audience became international for two reasons (Volk, 2005). First, Sōsaku Hanga was discovered by American military personnel and associated civilians who occupied Japan immediately after the war. They in turn promoted Sōsaku Hanga to others in the west either by word of mouth or in print (e.g., Statler, 1956). Second, Sōsaku Hanga artists began to participate in international exhibitions and competitions where their work was well received. An international commercial market developed for Sōsaku Hanga-style prints and they are now sold worldwide for wall decoration.

Sōsaku Hanga artists who chose flowers and birds as subjects for some of their prints are listed in Table 3.16. All but one of these artists (i.e., Un’ichi Hiratsuka) were most active after World War II. The number of flower-bird prints made by most artists was relatively small (i.e., less than ten).

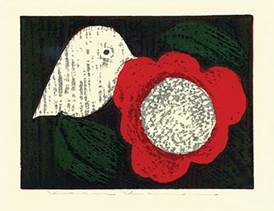

Four examples of flower-bird pictures drawn by these artists are shown in Figure 3.27 to illustrate features of the Sōsaku Hanga style. The artist’s creativity is evident in both the shape and color of objects. Shapes of flowers and birds were purposely distorted (Figure 3.27a) or simplified (Figure 3.27b,c) more often than they were drawn accurately (Figure 3.26d). In addition, the size of flowers was sometimes exaggerated for effect (Figure 3.27a,b). These shapes were formed by applying areas of pigment, typically without a black outline (Figure 3.27a,b,d). Full color was used for most pictures but the color scheme was rarely true to life (Figure 3.26a,b,c). Color was applied evenly creating a flat, two-dimensional picture. Revealing the inner spirits of flowers and birds was not a priority for Sōsaku Hanga artists. Birds were rarely shown in an active position or with rough body-edges (none in Figure 3.26). Nor were birds usually arranged diagonally with flowers (none in Figure 3.26).

Figure 3.27. Four examples of flower-bird pictures drawn by Sōsaku Hanga artists.

Starting in the 1860s the Japanese government promoted western individualism which gave people more freedom and encouraged self-expression. To maximize self-expression in woodblock print making, some artists adopted a new practice of cutting woodblocks and printing pictures themselves. Prints made by these artists were called Creative Woodblock Prints (i.e., Sōsaku Hanga), in part to distinguish them from prints made by contemporary Nihonga artists, and also to emphasize the artists’ goal of creativity through self-expression. In the latter respect Sōsaku Hanga artists were similar to artists of the older Nanga School who also valued self-expression and creativity. These two characteristics are revealed through their deliberate use of an amateurish style to draw objects. Shapes of flowers and birds were often distorted or simplified. Of the pictures included in this analysis, only 30% of Sōsaku Hanga (SH) pictures and 31% of Nanga (Na) pictures had flowers and birds drawn accurately compared to 82% for Nihonga (Ni) pictures. In addition, the color scheme was not usually accurate (i.e., 31% SH and 12% Na pictures with accurate color versus 60% for Ni pictures). Sōsaku Hanga artists used multiple colors but many were not true to life. Colors chosen by Nanga artists were more often true to life but too few colors were used to reproduce accurately the color schemes of flowers and birds. Nanga artists applied color unevenly which gave objects a blotchy appearance. Sōsaku Hanga artists applied color more evenly but it made objects look two-dimensional instead of three-dimensional. Sōsaku Hanga and Nanga artists also differed in their use of artistic devices to help reveal the inner spirit of flowers and birds. Revelation of spirit was much less important to Sōsaku Hanga artists than to Nanga artists, reflecting the underlying western versus Chinese art philosophy of the two styles. For Sōsaku Hanga pictures included in this analysis, birds were shown in an active position on 37% of pictures, with rough body-edges on 9% of pictures and arranged diagonally with flowers on 49% of pictures. The percentage of Nanga pictures with these features was much higher (i.e., 71% with active pose, 56% with rough body-edges, 77% on diagonal). Nanga (Na) artists also left the shape of flowers and birds incomplete to simulate rapid movement more often than Sōsaku Hanga (SH) artists (i.e., 42% Na versus 8% SH of pictures).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Next Chapter or Back to Guides

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||